Eighty years ago, a significant chapter in military and social history began. The 6888th Central Postal Battalion—better known as the Six Triple Eight—was the only Black Women’s Army Corps (WAC) unit sent overseas during World War II. Their story, now brought to life in Tyler Perry’s Six Triple Eight, illustrates the complexities of military service during a segregated era, highlighting both their contributions to the war effort and their challenges.

This post begins a series commemorating their 80th anniversary. As we approach January 9th, a notable milestone in their story, we’ll explore the events that led to their overseas training at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, and the origins of a unit that shaped history—both on screen and in reality.

Disclaimer:

This series includes historical terminology, such as “colored” and “Negro,” which were commonly used during the time period being discussed. These terms are presented in their historical context to reflect the language of the era and the records of the time. While these terms are outdated and may be offensive today, they are used to accurately represent the historical experiences and documents of the 6888th Central Postal Battalion.

A New Role for Women

When the United States entered World War II, the military was unprepared to integrate women into its ranks. The establishment of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) in May 1942 marked a shift, allowing women to serve in non-combat roles.

However, the U.S. Army’s segregation policies extended into the WAAC. Black women, capped at just 10.6% of recruits, trained in separate facilities, ate at segregated tables, and often served in roles unrelated to their skills. For many, this was their first encounter with the entrenched systemic racism within the U.S. military.

Amid these constraints, individuals like Charity Adams emerged as leaders. Adams, one of the first women to join the WAAC, quickly advanced through the ranks. A former teacher from South Carolina, she later commanded the 6888th, demonstrating both the challenges and opportunities for Black women in the military during this period.

The Role of Mary McLeod Bethune

The creation of the 6888th Central Postal Battalion was influenced by figures outside the military, including Mary McLeod Bethune, portrayed by Oprah Winfrey in The Six Triple Eight. Born in 1875 to formerly enslaved parents, Bethune’s early experiences in the Reconstruction-era South shaped her dedication to improving education and opportunities for Black Americans.

Bethune’s career began in teaching, but her impact extended into national policy and civil rights. She founded her own school in Daytona, Florida, and gained recognition for her work with civil rights organizations. Her connections to prominent figures, including Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, allowed her to advocate for systemic change on a larger scale.

In 1935, Bethune founded the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW), an organization focused on advancing the rights of Black women and their communities. The NCNW became a key advocate for equality within the WAAC, lobbying against segregation and pushing for overseas opportunities for Black Wacs.

Though Bethune was ineligible to enlist due to age restrictions, she played a critical advisory role. Her assistant, Harriet M. West, joined the first group of WAAC officers and worked directly with Corps leadership. Bethune’s influence and her relationship with Eleanor Roosevelt led to sustained pressure on WAAC leadership to expand opportunities for Black women.

The Fight to Serve Overseas

Practical planning for the employment of Waacs overseas began on August 1, 1942—before the initial classes had even graduated training. War Department Cable 2854 called for four WAAC Companies to be assigned to the European Theater of Operations (ETO)—two companies of white Waacs and two companies of Black Waacs. While the white units were to be assigned to Services of Supply (SOS) and Theater headquarters, the Black women were to be given the vague assignment “to meet the particular needs of the theater.” However, the systemic racism of the military prevented this plan.

On September 18, 1942, Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower wrote to Maj. Gen. John Clifford Hodges Lee, SOS’s Commanding General, and denied the cable’s request. According to his communications with WAAC Deputy Director Major Noel Macy, the “prestige of the corps” stateside and abroad would be negatively impacted by a proportion of Black Waacs exceeding 30% of the total. A second request in late September amended the numbers to eight companies of white Waacs and four companies of Black Waacs, who would be assigned to areas with large numbers of Black GIs. This was countered with a proposal for eleven white WAAC units.

By June 1943, a month before the 1st WAAC Separate Battalion landed in the UK (the first unit of Waacs assigned to the ETO), a letter from the Chief of Administration, G-1, ETO, stated, “There is some doubt as to whether colored companies will ever be utilized in this theater.”

By 1944, advocacy from groups like the NCNW and the NAACP had brought the issue of overseas service for Black Wacs to the forefront. Still, requests for Black units to serve overseas were initially denied under the pretext that their presence was not necessary for “morale purposes.”

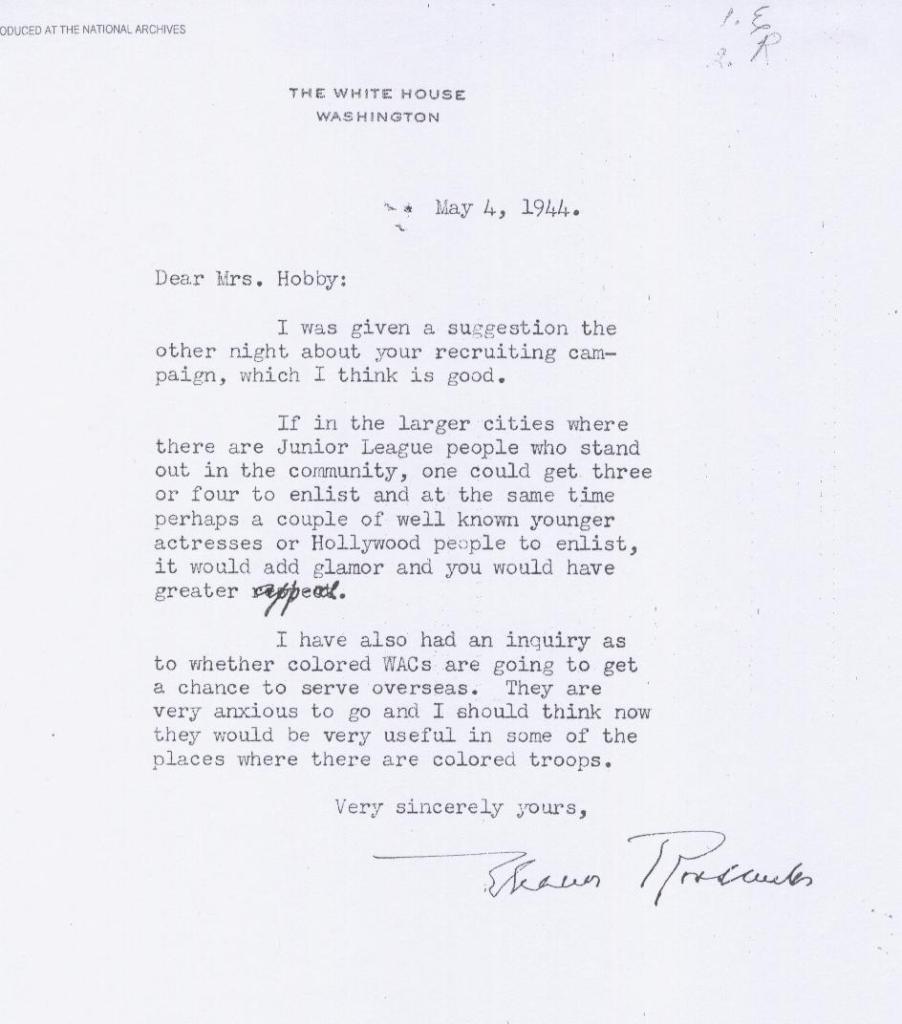

Bethune’s advocacy, supported by Eleanor Roosevelt, helped shift this perspective. In May 1944, Roosevelt wrote to WAAC Director Oveta Culp Hobby, emphasizing the desire of Black Wacs to serve overseas. These efforts finally proved successful on November 9th, 1944, when Headquarters, ETOUSA, sent cable requisition Number 61973 to the War Department. The requisition called for 31 officers and 824 enlisted women to be assigned to a provisional unit designed to be assigned to handle a Central Directory Postal Service.

On December 14, 1944, the War Department’s Negro Troop Committee reported that 300 Black Wacs had been ordered to report to the Third WAC Training Center at Fort Oglethorpe by January 15, 1945, to be followed by an additional 500 women.

Key members of the 6888th were carefully selected to ensure the unit would be beyond reproach in their conduct and performance. This was seen as essential to counter potential criticism. Charity Adams Earley wrote that her initial reaction when Col. Frank McCoskrie asked if she would be willing to serve overseas was one of disbelief, but once she began working on the selection of the battalion, she became more excited at the prospect.

A Mission That Mattered

The assignment awaiting the 6888th was unprecedented: to clear a backlog of mail that had accumulated over nearly two years in the European Theater of Operations. This mail represented a crucial link between soldiers and their families, with its delivery being vital to morale.

On January 9, 1945, the women of the 6888th began their training at Fort Oglethorpe. The experience prepared them for the logistical challenges they would face overseas and represented a significant step forward in their historic mission.

Coming Next

In the next post, we’ll explore the transition to training at Fort Oglethorpe.

The 6888th’s service reflects the broader complexities of military integration and the intersection of race, gender, and wartime necessity. As we commemorate their 80th anniversary, we aim to provide a detailed and nuanced understanding of their contributions and legacy.

Leave a comment